Your microbiota’s previous dining experiences may be making your New Year’s diet less effective

Your microbiota’s previous dining experiences may be making your New Year’s diet less effective

As most of us start trying to improve our diet for the start of the year, new research from Washington University in St Louis may shed light on why attempts to get healthy might be slower than we might hope.

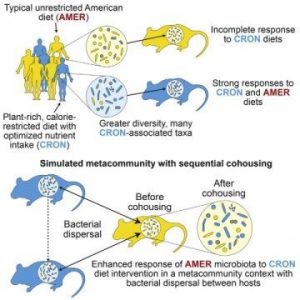

The study, published in the December 29 edition of Cell Host & Biome, explored why mice that switch from an unrestricted American diet to a healthy, calorie-restricted, plant-based diet don’t have an immediate response to their new program – finding that certain human gut bacteria need to be lost before the full range of benefits of a healthier diet plan can occur.

The researchers studied how diets can influence gut bacteria by taking fecal samples from people who followed either a calorie-restricted, plant-rich diet and from people who followed a typical, unrestricted American diet. People who followed the healthier, restricted, plant-rich diet were observed to have a more diverse microbiota (a wider range of types of gut bacteria).

The researchers then colonised groups of germ-free mice with the different human donors’ gut communities and fed the animals the donor’s native diet or the other diet type. Although both groups of mice responded to their new diets, mice with the American diet-conditioned microbiota had a weaker response to the plant-rich diet.

To work out which microbes were likely to enhance the response of the American diet-conditioned microbiota, the researchers then set up a series of staged encounters between the mice. Animals harbouring American diet-conditioned human gut communities were sequentially co-housed with mice colonised with microbiota from different people who had consumed the plant-rich diet for long periods of time. Microbes from the plant diet-conditioned communities made their way into the American diet-conditioned microbiota, markedly improving its’ response to the plant diet.

“We need to think of our gut microbial communities not as isolated islands but as parts of an archipelago where bacteria can move from island to island. We call this archipelago a metacommunity,” says lead researcher Nicholas Griffin. “Many of these bacteria that migrated into the American diet-conditioned microbiota were initially absent in many people consuming this non-restricted diet.”

Although the researchers are excited that their research has the potential to help guide the development of healthy dietary strategies, they stress that more research is still needed to understand the exchange of microbes between people (but in the meantime, maybe it’s time to start co-habiting with your healthiest friends or family?).

“We have an increasing appreciation for how nutritional value and the effects of diets are impacted by a consumer’s microbiota,” said the researchers. “We hope that microbes identified using approaches such as those described in this study may one day be used as next-generation probiotics. Our microbes provide another way of underscoring how we humans are connected we are to one another as members of a larger community.”

Journal Reference:

Griffin N.W. et al. Prior Dietary Practices and Connections to a Human Gut Microbial Metacommunity Alter Responses to Diet Interventions. Cell Host & Microbe, 2016; DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.12.006